18 Jan Digital Trust – towards a more sustainable approach to personal data

Advances in information and communications technology, combined with exponential growth in data, have given rise to a more empowered consumer. Online users have learned how to compare services and their prices. They have found ways to make their voice heard, by providing feedback and therefore stepping into the territory of traditional brand communications. The downside of this is that the customers themselves, together with their preferences, needs and identity, have become more transparent. Preventing personal data from being processed is no longer a realistic, feasible approach in an Internet enabled society. It is rather increasingly important to understand how businesses should use disclosed data and how control over this data can be brought back to the individual. Today, the majority of digital businesses rely on an ad-centric, data driven business model. However, they have missed and often intentionally neglected the opportunity to establish a trust-based relationship with their customers. Users are forced to blindly trust in fair and lawful conduct. The steady erosion of privacy results in pervasive concerns regarding the use of personal data. In a world where privacy is withering away like ice in summer, understanding and building online trust are essential business capabilities. Digital trust is moving further away from the traditional concept of trust in people and becoming more similar to institution-based trust. This article introduces a comprehensive, strategic approach to understanding digital trust. The iceberg model is used to pay attention to different component of trust and provides a framework that allows marketing professionals to understand how trust is built.

As the data volumes grow, business analytics capabilities become more and more powerful. This underlines the hypothesis that true privacy on the Internet does not exist – any more. Even if a service provider guarantees privacy, users bear a certain risk that their personal data are mined and brought in context with their identity at a later stage. Modern analytics may inadvertently make it possible to re-identify individuals over large data sets. The numbers of data points that can be used to build a rich profile of users are countless. An insurance company can for example monitor the characteristics of a prospect’s keyboard usage (speed of typing and moments of hesitations, typing pressure and usage of small caps versus uppercase), which can reveal relevant information. Hesitation, for example, shows limited decisiveness and therefore may give hints regarding a customer’s willingness to pay. Individuals can often be re-identified from anonymised data because their personal data often narrows possible combinations down and finally leads to the individual. Thus, online privacy is at risk. As a natural reaction to the described developments, consumer concerns regarding the disclosure of personal data are increasing. However, the motivation of online businesses to protect their users privacy and to act as advocates for the customers is often surprisingly low. It is usually limited to pursue objectives in marketing, such as avoiding reputation risks. Businesses have to change their attitude in order to be successful in the future.

Studies conducted by leading management consultancies reveal that the perceived confidence in the security of personal data is alarmingly low. Only about one third of the respondents in Europe trust in the security of their data (Accenture, 2014). The research also identifies significant differences in the acceptability of data use and confidence in the security of personal data between countries. While respondents in India show the highest confidence (72%), only one in four Japanese users think that their data is safe. Users consider certain data types, such as credit card data and financial data, as the most private. Data types that are not directly linked to the identity, but only to the profile of a user (such as age and gender) are perceived as less delicate. But despite consumers’ distrust, there is hope for data scientists and marketing specialists; Although today’s internet users are very much concerned about privacy and the integrity of their business partners, two third of consumers globally are willing to share additional personal data in exchange for additional services or discounts. European companies that successfully establish a trust-based relationship with their customers can increase access to consumer data by about ten times (BGC, 2013).

How digital trust reduces complexity

Ever since the World Wide Web became a global phenomenon, scientists from a wide range of disciplines have tried to make the trust construct comprehensible. These studies all build on the broad scientific work that originates from a more analogue world. Deutsch has developed one of the most fundamental definitions for trust (1962): He defines a framework in which an individual faces two aspects. First, the individual has a choice between multiple options that result in outcomes that are perceived as either positive or negative. Second, the individual acknowledges that the actual result depends on the behavior of another person. Deutsch also mentions that the trusting individual perceives the effect of a bad result as stronger than the effect of the positive outcome. Thus, trust is built, if a person assumes that the aspired beneficial result is more likely to occur than a bad outcome. Important factors in the trust equation are missing control, vulnerability and the existence of risk (Petermann, 1985). The existence of multiple options and diverse scenarios lead to ambiguity and risk. Faced with numerous possibilities, individuals must reduce complexity in order to eventually make a decision and not to fall into the trap of analysis paralysis. Trust is such a mechanism that reduces social complexity. It plays a central role in helping consumers overcome perceptions of risk and insecurity (McKnight, 2002). This context is best captured in the definition of trust developed by Mayer, Davis and Schoorman (1995: 712):

“Trust is the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party“.

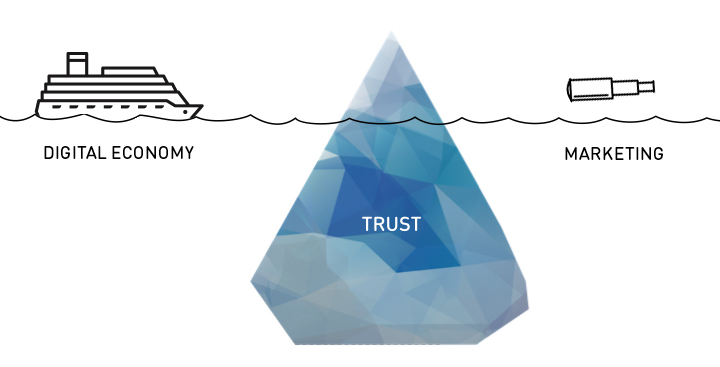

A trust model that resembles the shape of an iceberg

In the context of trust, the iceberg metaphor works in many different ways: First of all, trust must be seen as a precious good. It is hard to build, but can be lost very quickly. This makes it both a key differentiator to win against the competition and a potential pitfall that can easily destroy organizations. The Volkswagen emissions scandal has demonstrated how quickly trust is lost. It showed that even strong brands from traditional brick-and-mortar businesses can become severely damaged. The Internet accelerates this process. Bad news or reviews are spread at light speed around the globe and once negligible pieces of information can cause harmful shitstorms to spiral out of control. Like an iceberg at open sea, trust issues must be recognized early and marketers need to sail elegantly around such perils. On the other hand, trust is vital. Ongoing melting of the polar ice caps will inevitably raise the sea level and put coastal areas in danger. Similarly, if the trust factor is neglected, organizations are missing out on potential business opportunities and putting themselves at risk to be sunk by the competition.

Second, the sheer size of an iceberg usually remains unknown to the observer. This is due to ice’s density being less than liquid water’s density. Hence, only one-tenth of the volume of an iceberg is typically above the water level. This resembles the fact that most of the determinants of trust are less known, not understood or simply invisible. Moreover, it is difficult to manipulate those constructs. Trust therefore is often built when no one is looking. For companies this means that there are limited but important options to influence the information asymmetry in digital markets.

Just like the processes of freezing water and forming an iceberg take a lot of time, the process of building trust usually takes time. The primary way of gaining trust is to earn it by developing and nurturing a relationship with customers and future prospects. Companies can and must have control over the quality and intensity of the customer experience if they want to influence the level of trust of the customer. Opportunities to shape the experience exist at any touchpoints in the customer decision lifecycle. This model however focuses on understanding and engendering initial trust.

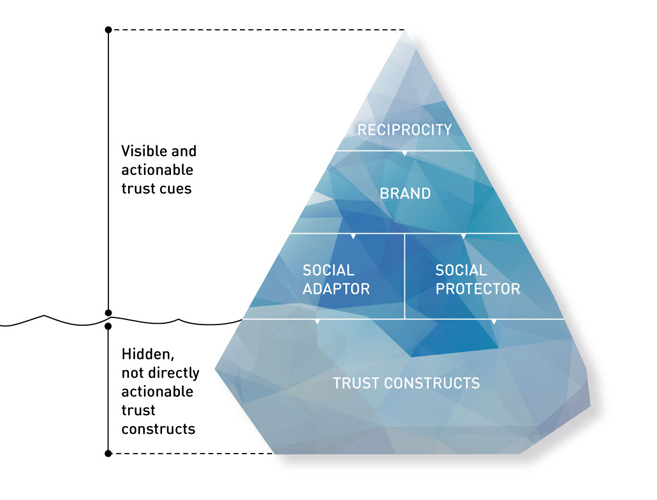

The iceberg trust model differentiates between two major components that influence formation of initial trust: Trust constructs and cues/signals. Trust constructs refers to elements of the iceberg that are usually under water. They represent the schemata that unconsciously steer our behavior. Constructs represent mechanisms driven by our hot, affective system. Cues or signals refer to strategic areas and design patterns companies apply to engender trust. They are above the surface and allow for reducing information asymmetry.

The iceberg model suggests four clusters of trust cues that sit at the tip of the iceberg: Reciprocity, brand, social adaptor and social protector. Each cluster holds again a set of trust signals or trust design patterns (please refer to the online documentation on iceberg.digital® for details on trust design patterns) that can be considered by marketing professionals in order to engender trust.

- Reciprocity: A social construct that describes the act of rewarding kind actions by responding to a positive action with another positive action. A fair level of reciprocity is reached through transparent exchange of information for appropriate compensation.

- Brand: A company makes a certain commitment when investing in its brand, reputation and awareness. Capital invested into a brand can be considered a pledge that is at stake with every customer interaction and every transaction.

- Social adaptor: A strategic element that connects the cues with the base of the iceberg as an interface to the construct of institution-based trust. The social adaptor holds innovative strategic elements in the technological space that influence how consumers perceive structural assurance and situation normality. Online users that perceive high situation normality would belief that, in general agents in the environment have the required trust building attitudes; competence, benevolence and integrity.

- Social protector: The empowered customer has identified online review systems as a very intuitive, quite robust and therefore useful source of information for decision-making. Trust design patterns within this cluster can support users to avoid interactions that result in a loss. They can help to overcome ‘tragedies of the commons’ and create social benefits.

Why digital minds do not act rationally

Giving away personal data in a situation of uncertainty and without adequate compensation seams to be an irrational behavior. This contrasts sharply with the traditional economic theory of a rationally acting individual, the Homo Economicus. Neuroeconomists and modern behavioral economists have demonstrated that consumers are, in fact, not rational in their decision-making. The same can be said for the consumer in the digital space and here are the reasons why.

An understanding of the basic structure and mechanisms of the human brain is key to understanding the digital customer’s mind. The most fundamental insight in this context is the fact that our thinking relies on two distinct systems. The first system operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control. The second operates more slowly and allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it. Popular science names these systems the cool and hot thinking (Mischel, 2014) or simply system 1 and system 2 (Kahneman, 2011).

When prompted to provide personal data online, a customer will always process information though the two systems. It is key to know that the cool and the hot system always have an influence on and compete with each other. If we face a stressful situation, the cognitive system powers down and resources are allocated to the hot system. Digital consumers need to be able to resist temptations and to cool allures down in order to be able to make rational, deliberate decisions. Professor Mischel identifies a set of powerful strategies that allow individuals to increase their level of self-control. Among these is the strategy to reflect on one’s own situation through the eyes of another. The cool system can more easily be activated when a hot decision is made for another person. This may explain the success of online recommendations and third party endorsements. Users may make wrong purchase decisions, but their online reviews (e.g. on Tripadvisor) are very specific and helpful for others to prevent the same mistakes. Reviewers are able to conceive meaningful recommendations, even if they have not bought or consumed the service or product themselves. An increased sensitivity of online customers regarding privacy and higher competence in dealing with personal data support the activation and therefore the weight of the cognitive, so the cold, system. The evolution of the digital mind will make it increasingly more difficult to extract an email address from a visitor with promises of a chance to win an iPhone. Already, users have become more willing to deliberate a truly strong password instead of a 4-digit number – which was probably the user’s birthday. Building initial trust relies heavily on the evaluation of existing schemata. Such schemata describe a pattern of thought or behavior that organizes categories of information and the relationships among them. Schemata can be seen as memory traces. Part of the journey towards a more sustainable approach to personal data is to benevolently support customers in building new competence in dealing with data and eventually to develop these schemata’s.

Another interesting perspective originates from Behavioral Economics. Economists provide a set of theories that contribute to an answer on how people act under uncertainty. This discipline has been dominated for years by the picture of the homo economicus – an individual that acts fully rationally without being influenced by emotions. The homo economicus draws on the cool system as described above to align his decisions fully on the maximization of benefit and minimization of cost. However, friends, feelings and preferences influence even the coolest character in his behavior. Our brain is “hard-wired” to socially interact with other human beings. And all these interactions lead to information and eventually schemata that influence our decisions made by the hot system even before the cool system has a chance to kick in. Empowered by technology, consumers have become networked minds, social decision-makers, more than ever before (Helbing, 2015) and so more vulnerable to ‘hot’ influencing factors.

The traditional economic concept of the rationally acting individual turns out to be incorrect. Decision-making can best be explained with the theory of bounded rationality (Simon, 1997). According to this, people tend to make decisions with particular biases. Understanding these biases gives insights into the mind of the consumers and eventually reveals strategies for marketing to influence costumer decisions. In particular, the prospect theory helps to explain several behaviours observed in economics (Kahneman/Tversky, 1979). The different perspectives on looming gains and losses may explain why the same person may buy both an insurance policy and a lottery ticket. Please refer to our online documentation on iceberg.digital® for more insights about cognitive biases.

Required capabilities to engender digital trust

The ability to establish a mutual, honest dialog and a long-term partnership with customers will be central to defining the winners of tomorrow. In order to engender trust and to build a true partnership with their customers, companies need to go a step further in the evolution of marketing. MIT Sloan Professor Glen Urban has conceived an interesting approach that is fully oriented to the characteristics and needs of the empowered customer. Urban describes an advanced form of market-orientation that responds to the new drivers of consumer choice, involvement and knowledge. Customer Advocacy aims to build deeper customer relationships by earning new levels of trust and commitment (Lawer et al., 2006). It is all about the development of mutual transparency, dialogue and partnership with customers. Customer Advocacy uses the mindset and tools of the CRM-approach, as well as orientation towards total quality and customer satisfaction as a foundation. Companies following this strategy act as honest and unselfish advocates for the customer. This includes providing the customer with the best offer, even if it comes from a competitor (Urban 2005). In return, the consumer offers trust to the company and is more willing to share information.

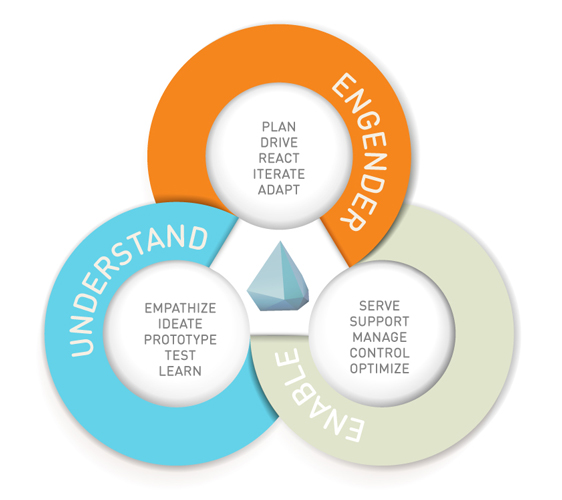

There is no standard process for identifying and solving trust issues. However, in order to leverage digital trust as a currency and as a key differentiator for future success, companies can build and practice three major business capabilities. Engendering the belief of competency, benevolence and integrity constitutes a poorly bounded problem. These are problems that are essentially unique. Solutions to these “wicked” problems are not true-or-false, but better or worse. It therefore requires a dynamic approach to problem solving. Furthermore, it requires an effective approach that eventually identifies often hidden problems. Last but not least, it requires an empathy-based, human centered process that focuses on actual user needs. All of these requirements are met with the Design Thinking methodology by the Stanford Design School.

- Understand: Businesses must be able to find their customers’ issues and therefore to correctly understand their situation. Although analytics can support this step, businesses have to rely rather on “thick” than on “big data”. Whereas Big Data can give insights into customer behavior on a massive scale, Thick Data aims to reveal underlying motivations, intentions and emotions. Specific techniques such as interviews, contextual research and usability studies can help collect data required for empathizing, ideating, prototyping, testing and learning.

- Enable: Answer the question about the “why?” first. Then conceive plans for the “what?” and the “how?”. It is critical to align all trust strategy measures to clearly articulated business objectives. Companies may build a value tree that clearly structures potential value drivers and outlines objectives. These objectives will be used to evaluate projects that result from ideation and prototyping. A set of trust metrics will help to build the business case and to control initiatives. Furthermore, guiding principles and a solid code of conduct need to be established.

- Engender: Trust is earned over time and further shaped on every touch point within the customer life cycle. Companies must actively manage their roadmap of trust initiatives. Feedbacks from implementation need to be considered and may require further actions and adaptations. Engendering trust is an iterative process.

The “balancing act” of competing business interests and privacy requirements will be of increasing importance in the near future. Marketing often takes advantage of the consumer’s bounded rationality and their well known cognitive biases. Such a rather opportunistic approach in digital markets is not sustainable. Electronic markets have the potential to substantially reduce information asymmetry and transaction costs. They offer effective opportunities to gain insights into needs and behaviours of customers. Extracting these insight requires respectful and farsighted handling of personal data. The digital revolution with its explosive growth of data and system complexity is about to transform industries again. In order to harness the potential of data, the digital economy and its data driven business models must get on a journey towards trust-based customer relationships. It all starts with a better understanding of digital trust.

Please visit www.iceberg.digital to learn more about digital trust.

About the author:

Daniel Glinz is an experienced management consultant and digital strategist. With broad academic background from leading management and design universities and a strong link to investors and start-ups, Daniel combines groundbreaking conceptual work with the ability to shape and actually transform businesses. Find out more about digital transformation consulting on www.glinz.co.

References:

Accenture, 2014, CMT Digital Consumer Survey.

BCG, 2013, Global Consumer Sentiment Survey. In: The trust advantage, How to Win with Big Data.

Deutsch, M., 1962, Cooperation and Trust: Some Theoretical Notes. In: Marshall, Jones R.: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press: 275-318.

Helbing, D., 2015, Thinking Ahead, Essays on Big Data, Digital Revolution, and Participatory Market Society, Springer

Kahneman, D., Tversky, A., 1979, Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 47 (2): 263–292.

Kahneman, D., 2011, Thinking, fast and slow, Penguin.

Lawer, C., Knox, S., 2006, Customer Advocacy and Brand Management. Journal of Product & Brand Management 15 (2): 121-129.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., Schoorman, D. F., 1995, An integrative model of organisational trust. Academy of Management Review 20 (3): 709-734.

McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., Kacmar, C ., 2002, Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Information systems research 13 (3): 334-359.

Mischel, W., 2014, The Marshmallow Test: Why Self-Control Is the Engine of Success.

Petermann, F., 1985, Psychologie des Vertrauens. Salzburg: Müller.

Simon, H. A., 1997, An empirically-based microeconomics. Cambridge University Press.

Urban, G., 2005, Don’t Just Relate – Advocate!: A Blueprint for Profit in the Era of Customer Power. Wharton School Publishing.

Photo: Kuromon Ichiba Market, Ōsaka-shi, Japan, by Andy Kelly on unsplash.com

This article has initially been published in the Center for Digital Business Yea(h)rbook 2015,

ISBN: 978-3-03805-041-4 (Print), 978-3-03805-191-6 (PDF), 978-3-03805-192-3 (ePub), 978-3-03805-193-0 (mobi/Kindle)

No Comments